Days before talks that could decide its future role in setting the rules for global commerce in an era of rising protectionism, the World Trade Organization is snagged on what to do with its “non-meetings”. That’s what some jaded delegates at its vast headquarters on the banks of Lake Geneva in Switzerland have called the hundreds of unofficial negotiations taking place on fixing the WTO’s dispute system as part of Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala’s drive to make it “fit for purpose” by 2024.

At least 100 ministers will gather in Abu Dhabi on Feb. 26-29 for the WTO’s 13th ministerial conference once dubbed the “reform ministerial”. In a sign of wider divisions plaguing the body, delegates cannot even agree to “formalise” the talks that aim to revive the WTO’s top appeals court, known as the Appellate Body, which has been idle since 2019 due to U.S. blockages of judge appointments. As such, trade experts say the best hope is a feeble commitment to keep negotiating on this and other key reforms like reviewing poor countries’ trade terms in Abu Dhabi.

They cite other obstacles as the U.S. presidential election in November, which they fear is constraining Washington’s appetite for WTO policy moves, criticism from developing states and the surprise exit of the talks’ key facilitator Marco Molina, meaning a “last chance” for reform may have been lost. China’s ambassador Li Chenggang said he was disappointed at the missed opportunity to reform the WTO’s Appellate Body, which has more than 30 unresolved trade disputes. “This meeting is in the pre-existing context that the WTO is failing, useless, out of touch, unable to actually reform itself,” said the Paris-based International Chamber of Commerce’s Secretary General John Denton. “So, in that context, anything that just keeps the WTO going is probably considered a success.”

WARS AND ELECTIONS

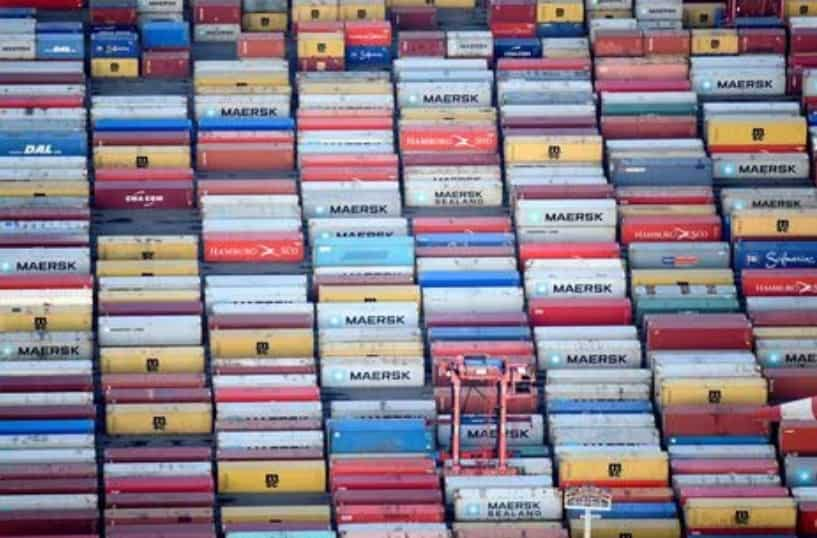

The free trade agenda that the 164-member WTO and its predecessor the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) have sought for nearly five decades to defend is under attack as never before. Free trade, its supporters say, has helped lift billions out of poverty. But critics say the WTO has failed to shape trade so that it narrows inequalities between rich and poor nations and help tackle new global challenges, not least climate change.

To be sure, the scope of what the WTO can achieve is limited by factors beyond its control such as wars, elections and geopolitical rivalries.

Trade fragmentation opens new tab has also sapped countries’ commitment to further trade liberalisation and data from Swiss-based trade watchdog Global Trade Alert show there were 3,488 protectionist moves in 2023 – fewer than during the COVID-19 pandemic years but above the average of the previous decade.

The widely-held perception that Washington is less motivated to land trade deals is another challenge. “In the past, the U.S. was more willing to trade away its short-term interest for the long-term gain of systemic construction,” said Dmitry Grozoubinski, executive director of trade policy think tank, the Geneva Trade Platform, naming its willingness to commit to lowering tariffs. “I think it is fair to say that, at the moment, the U.S. isn’t willing to make those kinds of trades anymore.” U.S. officials maintain that they are fully engaged with WTO issues. Trade Representative Katherine Tai said that U.S. leadership at the WTO was not about having the “loudest voice” but about “finding ways to build bridges”.

The tough atmosphere means prospects for getting deals on decades-long talks on agriculture and fisheries are seen as a long shot, while progress on new rules on environmental issues which are not part of the WTO’s mainstream mandate will likely be limited to future road maps. “We are no longer in the 1990s. There are no expectations for big conclusions,” said one trade delegate, though he reckons a fishing deal could still be reached.

‘DECISION-MAKING SCLEROSIS’

Changes to WTO rules require consensus which has always constrained its ability to reach global deals since it just takes one country to block an agreement. Only two have ever been reached: a partial fishing deal (2022) and the red-tape-cutting Trade Facilitation Agreement (2013). Faced with what former WTO director Keith Rockwell penned, opens new tab the WTO’s “decision-making sclerosis”, talks have splintered into smaller coalitions and many think this is the future.

A deal to remove development-hampering investment barriers is being sought by around 120 countries in Abu Dhabi. Even if all negotiations collapse next week, there is no risk to the existence of the WTO whose rules underpin about 75 per cent of trade and whose 1920s-era offices modelled on a Florentine Villa provides a tranquil venue to resolve frictions.”Can you imagine if those rules did not exist to govern world trade, what that would be,” Okonjo-Iweala told reporters last week. “If the WTO becomes irrelevant, everyone, including you and me, will be in trouble.”